|

Books

|

THE LIFE I dare say all novelists are asked how much of their fiction is really recycled autobiography. Given the high old time enjoyed by my heroines, I'm inclined to retort that chance would be a fine thing. However, I suppose that here and there fragments of real life must sneak between the cracks of the most improbable plot, so here's my attempt to tease the odd fact from the fiction. For anyone who only wants a few dates and place-names, however, the basic, dustjacket biog is in bold. Dead easy to skip the waffle.

Kate Fenton was born on the 14th of October 1954, too many years ago. In Failsworth, on the outskirts of Manchester, but was brought up with two younger sisters in Cheshire.

And bang goes any claim to gritty Northern credibility. Like all authors these days, I blame the parents. For everything. Instead of sticking around in smoky, mill-chimneyed Failsworth, they hoisted us up and out to suburban, tree-lined Cheshire. And did they abuse me, disown me, or at least indulge in a messy and acrimonious divorce to blight my impressionable years? They did not. What's a future novelist going to write about? Being startled by the neighbour's Yorkshire Terrier while cycling to the village shop is hardly bestseller material. Educated Convent of the Holy Nativity, Harrytown High School 66-73. Another blow. Catholic Convent Schools are famously rich sources for great literature, packing crippling neuroses by the satchel-load. But - here's the catch - only if you're a Catholic. I wasn't. On Sunday mornings I trudged down to Romiley Methodist Chapel, with the warm encouragement of my parents who were themselves vaguely atheist, but fancied a kid-free lie-in with a mug of tea and the Observer.

Still, while I may have wondered whether God (if He existed) preferred me singing hymns or saying rosaries, I wasn't blighted by my schooldays. Wouldn't say they were the happiest days of my life, mark you, but then I'm suspicious of people who claim to have loved school. Something unnatural about it, don't you think? I just mixed swotty subservience with sneaky subversion, reading Georgette Heyer under the desk and postponing homework until the last, which regularly left me scribbling essays at two in the morning. As I sweat to complete a novel against a deadline I feel I haven't come far. 1974-77, (by a miracle for which I still thank Methodist, Catholic and all other varieties of God) I went to St Hilda's College, Oxford - and while there are people who are miserable at Oxford, I wasn't one of them. Too amazed and grateful. A friend said she felt like a dazzled child given free run of a funfair. Quite. Within a term or so, I'd ditched my name (prissy Kathryn for snappy Kate), my northern accent (and, God, wasn't it hard remembering which A's to lengthen), a couple of stone (too busy to eat) and - rather more drastically - my chosen degree course.

I'd been given a place for music, you see, but instead read Philosophy Politics & Economics and Dick Francis whose books, interestingly, were prescribed by my philosophy tutor as an antidote to exam stress. I may never have touched another page of Wittgenstein, but I'm a passionate Dick Francis fan. Who says a university education doesn't equip you for life? Much as I'd like to claim I waltzed through three years of divinely

mad and bad Brideshead-ish decadence, though, I can't. You can take

the girl out of the suburbs, and all that. Neither beautiful nor

damned, I didn't just fail to inhale, I couldn't understand why

so many people seemed to roll their own cigarettes at parties. Even

so, with a ratio of 4 ½ After leaving university, she was (briefly) employed as a researcher (secretary) at the House of Commons, by a (foolishly trusting) back bench MP, who needed a Jaeger-clad gorgon to regiment his diary, constituency and filing cabinet (see Too Many Godmothers), not a ditzy ex-student who couldn't impose order on her own knicker-drawer. Perhaps I'd have done a better job if I'd been fired by political conviction, but all that had drawn me to the Palace of Westminster, after three years of studying political theory, was an idle curiosity to see how the place worked in practice. So it was never a serious career option and my employer and I parted on friendly terms (he was a nice man) before, I trust, his career suffered terminal damage. However, I'd like to make clear that, unlike Theodora Dunstan and the dishonourable Member for Tadstone West, our relationship was strictly business. Then, while cleaning a ladies' lavatory at the Edinburgh Festival… Ah, yes, Edinburgh. Where I was playing piano and bass guitar for a revue on the fringe. And at this point it occurs to me I've almost totally failed to mention music.

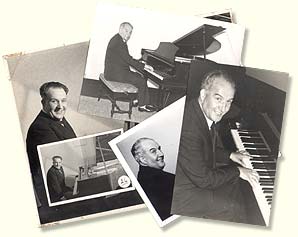

To say music was central to my life doesn't come near. I should explain that my Dad, Ray Fenton, was a professional musician. I won't say he hoped I was destined to play Wolfgang to his Leopold, but I was plonked on a piano stool while still in nappies. Not that I was pushed, still less was I a prodigy, it was just that, well, music was what I did. Like eating or breathing. Almost my earliest memory is of sitting under a piano, and I still find something obscurely comforting about the dusty-metal perfume of a Steinway's innards. So, alongside convent school, 66-74 I was despatched into town, where I studied piano at the Manchester School of Music with the extraordinary Sylvia Forbes - a five foot dynamo who combined Judy Garland's let's-do-the-show-right-here zest with Gracie Fields's black-pudding accent and the Queen Mother's passion for curvy hats and tip-tappy shoes. And we aren't talking a miserable hour a week of scales, arpeggios and Associated Board exams. Music with Mrs F was an all-consuming, concerts-and-festivals-every-weekend way of life. My sisters rode bikes and ponies and discovered boys. I played piano duets and trios and discovered Benjamin Britten.

Maybe that's why, when I'm asked whether I've always wanted to be a writer, I'm not sure of the answer. Sure, I've always been a fanatical reader - the type who'd dodge back below on the Titanic to grab something to read on the lifeboat - and, when I was young, the prospect of actually writing books for a living would have struck me as more magical, if rather less feasible, than flying to the moon. But everyone took for granted I'd end up doing something in the music world. Not as a performer, perhaps. For while Mrs Forbes swept us all along on her dancing tidal wave, she was clear-sighted. Only a very rare few, in her view, were fitted to become professional musicians - classical musicians, that is - and, for them, music wasn't a choice, it was a vocation, and a hard one at that. I wasn't one of the chosen. Sure, I could have found employment somewhere in the interesting hinterland surrounding performers, but after just a term of Palestrina & Co. at Oxford, I realized I wanted something other than music, something quite different - even if I didn't know what. That was why I switched to PPE. About which, incidentally, I knew nothing at all. Still, music remained as a sideline - as well as a very nice little earner. Yup, an earner. For while I may complain that my parents were quite uselessly kind and supportive to me throughout my blandly uneventful childhood - hell, they didn't even kick up a fuss when I jacked-in the music degree - I have to give my Dad credit for one thing. No sooner had I reached the age of fifteen, and could rustle a few competent-ish riffs up and down a keyboard, than in the best tradition of Dickensian fathers he sternly decreed it was time I worked for my pocket money.

As well as being a musician, you see, he had a sideline as a sort of theatrical agent. He booked artistes and acts for summer shows, cabarets, concerts, kiddies' parties and what have you round the north of England. Thus, Christmas 1969, I found myself in scanty evening dress hurtling up and down the mighty promenade at Blackpool (and let me tell you that famously fresh air is bloody fresh at midnight on Boxing Day), accompanying a glamorous soprano as she gave a twenty-minute cabaret spot in four or five jam-packed hotels a night. I mention all this only because if anyone has read Balancing on Air and scents an autobiographical connection they'd be absolutely right. Not that my soprano removed any garments. I've never played for a stripper, rather disappointingly, although I did, in later Christmases, get to vamp-til-ready while white rabbits were whipped out of hats and pink doves out of hidden pockets, also while swords were plunged down oesophaguses (oesophagi?), balloons were sculpted into giraffes and Scottish baritones, twirling a saucy kilt, belted out My Way. Interesting combo with convent school girlhood, don't you think? In subsequent years, I went on tour with pantomimes and musical shows, played at the ends of at least two piers, and generally subsidized my student income in far more colourful ways than stacking shelves at Tesco's. Variety of course was on its last gasp and beyond - somehow, the very word 'showbiz' sounds sweetly quaint now, don't you think? - but it was an education, not to say a treat, to find myself in the pit with magnificent old troupers like Nat Gonella, Addy Hall, or the Beverley Sisters (who were chauffeured to Yarmouth Pier nightly in a Rolls Royce) t'other side of the footlights. Echoes of all this can be found, not just in Balancing on Air, but Dancing to the Pipers, Too Many Godmothers, and certainly Picking Up. Perhaps it even explains why I've never attempted to write - correction, never succeeded in writing - a Serious Novel. I don't mean a novel without jokes, but one with, you know, A Message. All down to the parents again. I was reared in the entertainment business. Not a frustrated Hamlet, just an old time song-and-dance gal. Make 'em laugh, make 'em cry, and pull out all the stops for the finale. Still, enough philosophising and back to the point. Edinburgh. So, there I was in London, post-university and Palace of Wesminster, a hack pianist and lousy typist with a degree in PPE which famously equips you only to read Times leader columns, drifting round in a gloomy why-was-I-born? daze, when I heard that a bunch of medical students back at Oxford was taking a revue up to the fringe of the Edinburgh Festival - and needed a keyboard player. Curious, isn't it, the way so many doctors seem to have cherished theatrical ambitions in their youth? I dare say this lot are all fearsomely eminent consultants now, James Robertson Justice look-alikes floating Godlike in clouds of white-coated acolytes, but I can only say it's been an abiding nightmare of mine that one day I'd be knocked over by a bus and come round in hospital to find one of those amiable lunatics grinning down at me over a mask, scalpel in hand. The show - called Once Bitten - was not a major hit. Dire, to be honest, with audiences you could mostly have fitted into a telephone box, but it was good fun, even if we did have to subsidize our art by drawing social security and cleaning the cellar in which we were performing. (cf Dancing to the Pipers, and Picking Up). Thus the ladies lav where, on the floor, I found a torn page of The Daily Telegraph - a paper I wouldn't have been seen dead reading in those days - with a muddy footprint not quite obscuring an ad for researcher jobs in BBC Radio Wales. If I wanted to be grandiose, I'd say in that moment and that lavatory I found my destiny. And if anyone doesn't believe the story, I still have the newspaper. Thus, from 1978-1985, I worked for the BBC, first as a researcher, then as a features and documentary producer, in Radio Wales, the World Service and, latterly, Radio 4 in London - and loved it. I felt a more passionate sense of belonging to the BBC than I ever had to school or university or any other institution. I was employed at various times on Woman's Hour, Pick of the Week and Bookshelf, but the most intense pleasure came from making one-off programmes about anything from modern ghosts to medieval cookery to sea shanties. It was wonderful what they'd let you do in that pre-Birtian Garden of Eden. No question, the character of George in Balancing on Air is an amalgam of all that was grand and glorious and bonkers about the old ethos of public service broadcasting. And if you think she's exaggerated, you should have met the gang of venerable old soaks who used to prop up the bar at the Langham in the good old days. Once the BBC club, since sold off as a luxury hotel, of course, when Broadcasting House was overrun with Perrier-quaffing accountants and grey-suited management consultants and, God help us, focus groups and…. But, as I think I also said in Balancing on Air, old Corporation hands have always bemoaned a lost golden age of broadcasting which, mysteriously enough, ended the very day they collected their P45. I'm still a wireless addict. When Neil Kinnock said the luxury he'd take to Mr Plomley's Desert Island was Radio 4, he won my vote on the spot. I buy cars according to whether the radio gets long wave as well as VHF. When reading about Peter Mayle's Provence, or Chris Stewart's Spanish hillsides, I don't lust for the scent of lemons or the golden light filtering through the olive groves, I wonder whether you can get The Archers down there. No? Well, I'll stick in Blighty then, thanks very much.

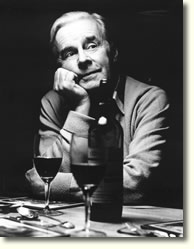

So why did I quit? Maybe because, in the BBC as in any other large organisation, there's only one way to get onwards and that's upwards. As I reached the end of my twenties I realized, in a rare flash of good sense, that I was not a manager. Not just was I lacking any talent for managing other people, (although that's never held anyone back in the BBC) I didn't want to preside over meetings and staff rotas and appointments boards. I'm an artisan, a craftsman, I like making things. Plus my poor old Dad was mortally ill - for a short while, I even ended up back on the cabaret circuit, playing for dates he couldn't make. Besides which, in 1984 I (had) met my future husband, actor Ian Carmichael. To be accurate, I'd employed him, to read some stories I was producing for Radio 4. So, one way or another in 1985 I left Broadcasting House and London, and joined Ian at his home up here in North Yorkshire, in the Esk Valley, a few miles inland from Whitby - a valley not in the least disguised as the Wragg valley in The Colours of Snow. In truth, I seem to have exploited the culture shock of uprooting from Clapham Common to the North York Moors so often in my books, I'm reluctant to go on about it here. If you're a welly-wearer yourself, you can imagine the pastoral delights - that heavenly moment of opening the back door of a morning to taste the air, hay-scented in June, a bonfire tang in December, of listening to the river, to the indignant croak of a pheasant, or just of revelling in the crystalline silence. If, on the other hand, you think that God wouldn't have invented supermarkets had He intended us to be on neighbourly terms with cows, then I'll admit it's twenty-odd miles to the nearest Marks and Sparks, and that kindred spirits are sparse and precious. Out in the sticks, there are a lot of chaps (and I choose my words advisedly) who think writin's a jolly sort of hobby for a gel. Doncherknow. Until I moved to the country, I'd never realized P G Wodehouse was a social historian. But don't be deceived. Even if I feel an odd twinge of nostalgia for the friendly yellow wink of a cruising London cab, I love it up here, with all the passion of a convert. When I arrived, though, it was only intended to be a sort of sabbatical. During which I was foolhardy enough to claim (well, I had to make some excuse for abandoning my chums in London) that I intended, at last, to Write A Novel. Big mistake. Writing, like dieting or giving up fags is something you should either do or not do, but you definitely shouldn't talk about it. I would creep upstairs to the typewriter I'd installed on an old dressing table - and stare wretchedly at the virgin drifts of paper. It took me until 1989 to complete the first novel which was published under my own name, The Colours of Snow. I've described in the notes to that book just why it took so long - curiously without mentioning chronic indolence or alcohol. No, no, I wrong myself. I'd actually written several First Novels, before I wrote my first novel, if you see what I mean. Still, all that's described elsewhere. Suffice to say, another five books have followed: Dancing to the Pipers (1993), Lions and Liquorice (1995), Balancing on Air (1996); Too Many Godmothers (2000), Picking Up (2002) — and The Time of Her Life (2020). You will notice the gap. The long, long gap. Eighteen years without producing a single book. What was I doing all this time? Well I was trying. Starting books, sometimes a couple of hundred pages' worth. And grinding to a miserable halt, chucking the poor dead manuscript in a box. I'm surprised the attic hasn't collapsed under the weight. I suppose you've got to call it writer's block. More about that curse on The Time of Her Life page. But during those wordless years I guess you could say I diversified - diversified big time. In an odd way, life imitated art. Picking Up, my last novel before The Block, was set on the local grouse moors. For research purposes, as a lifelong townie, I had pulled on wellies and even borrowed a spaniel, by way of cover, to join the tweedy throng on a shooting day. Not the grandees in the Range Rovers, you understand, but the workers in a tractor-trailer. It was supposed to be a one-day jaunt, but I went on to serve eight years in that beaters' waggon, on £20 a day and a can of lager. Happy times. Perhaps there were other reasons. My husband was growing frailer, and I had, perforce, had to take over just about all the day-to-day household stuff. Gardening, for starters. I barely knew a daffodil from a dandelion. My free time shrank. But I can't blame Ian. Other female novelists bring up six kids, rear rare-breed sheep, make their own marmalade and still turn out bestsellers. And then he died, just short of his 90th birthday but still, blessedly, very much himself, in the viciously cold February of 2010. Move on a year, to the even more viciously arctic February of 2011. The lane to this house was iced solid for three months. Now, as I mentioned earlier, my first novel ‘The Colours of Snow’ had been set in a snow-bound North Yorkshire valley, perfectly recognisable to locals as this one. The heroine - a smart, ex-London, blocked artist - falls obliteratingly in love with a funny, clever, diffident, thoroughly decent, couldn't-be-less-like-Heathcliff chap called Edward. Known as Ned. So who turned up at my door in the snow? Funny, clever, diffident, thoroughly decent. Edward. Or, in this case, Ed. And did I fall for him? Are you kidding? Although this truly bizarre instance of life following the path of fiction did have me wondering whether I hadn't gone completely crackers, that I'd somehow just dreamed him up and I'd wake to find a spaniel on the next pillow.

Happily not. We are married. And perhaps you can see why, when I did at long last find my way back to spinning a decent story, the result is called The Time of Her Life. | |||||||||||||||